Art, Activism, and the Women’s Movement in the UK 1970–1990

Exhibition at the Tate Museum

I was in London November 16-23rd for The Great British Striptease , an event produced by Victoria Rose featuring burlesque performers with sex work experience. The show was an incredible experience that I’ll talk about in another post.

While I was in town I went to the Tate Britain’s Women in Revolt! Exhibition, which was a mere 20-minute walk from where I was staying with my partner Jonny at the home of beloved friends Mat Fraser and Julie Atlas Muz, my former roomies. I’m excited to share a few quick photos with you!

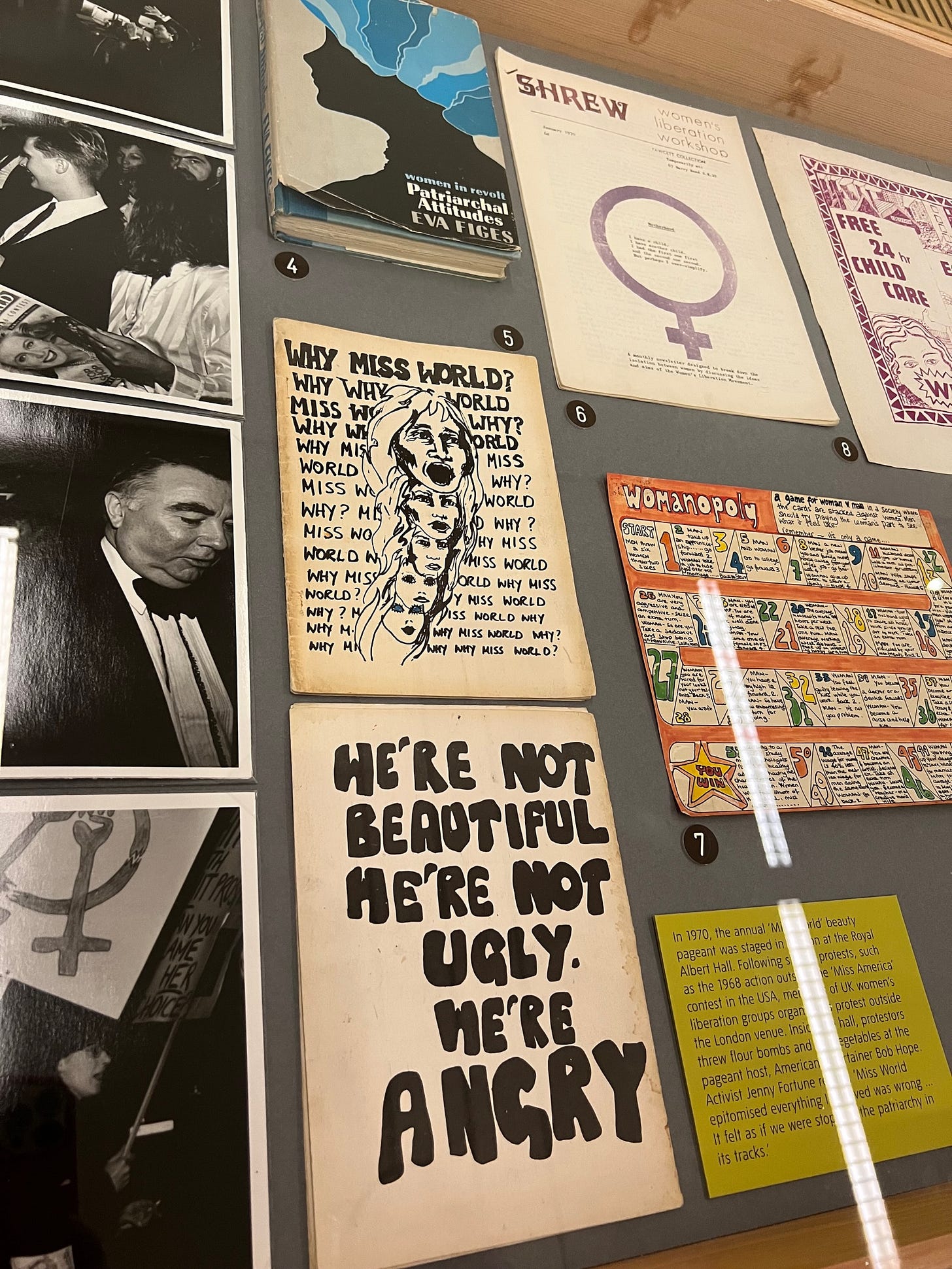

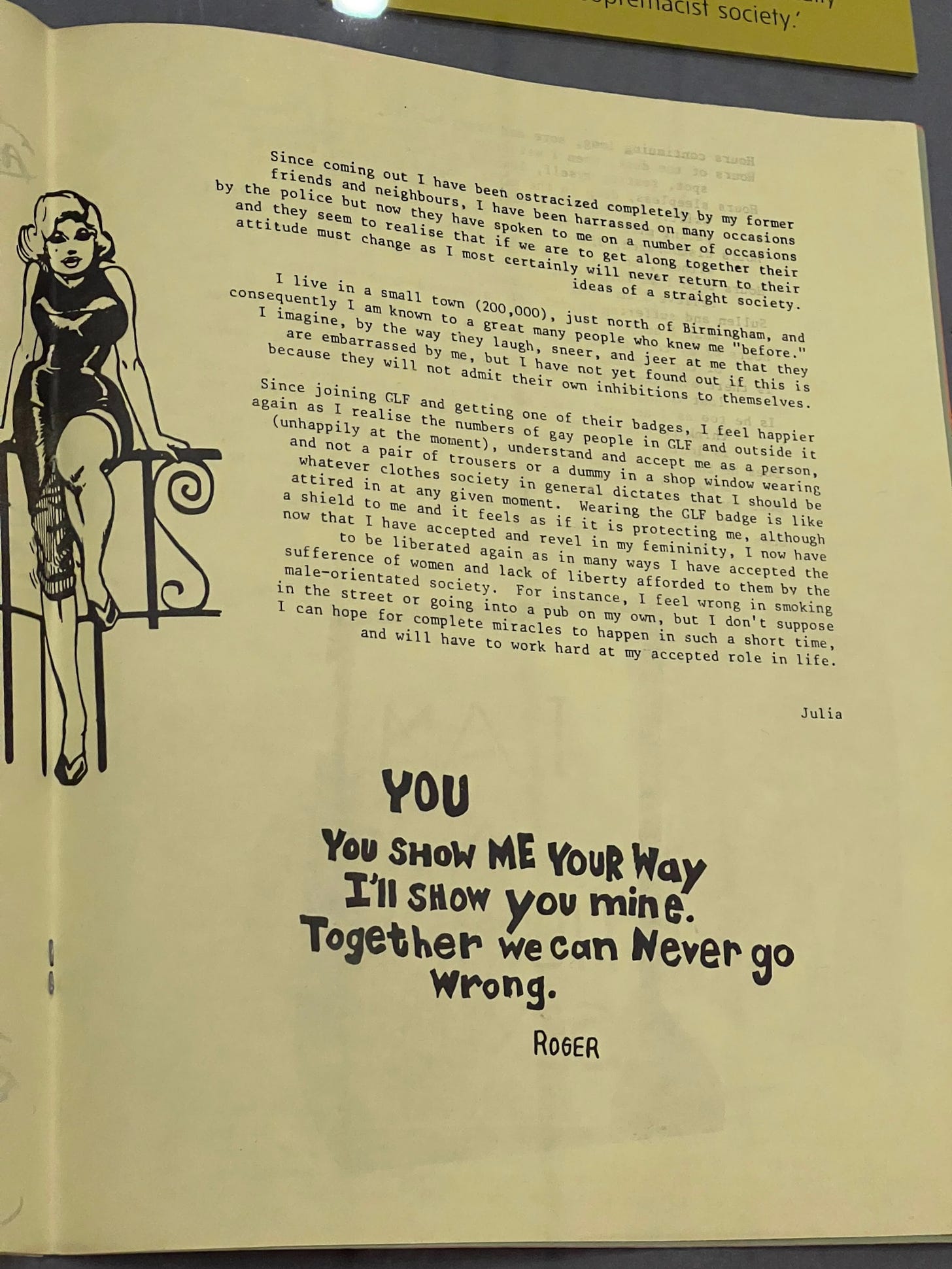

The exhibition was enormous and I could have easily spent another hour there if I hadn’t had to catch a train. It spread out over several rooms and flowed in mostly chronological order. I started at a display of photos, art, and video related to the era of the first National Women’s Conference in 1970, which “is widely considered the beginning of the women’s liberation movement in the UK.” I’m always fascinated by broad statements on placards at museums, because I know that the authors at some point have to make a decision to just say something, fully knowing it’s inadequate. “Widely considered” by whom? Is it possible for something that’s “widely considered” to be inclusive (ie, accurate)? If there’s one thing we all know about collecting history, it’s that any collection will have to be incomplete if it’s going to be shared in a finite way. An exhibition, as a physical digital site, is fixed in the moment of each viewing, even if it might be edited or expanded later on. There are always absent perspectives, some known and some unknown. This exhibition is about a history of rebellion – the movement was called “women’s liberation,” meaning women felt a need to be freed. But the question will be asked, “Which women, and from what?” (See https://www.nytimes.com/1971/08/22/archives/what-the-black-woman-thinks-about-womens-lib-the-black-woman-and.html) I often find it incapacitating to try to get it perfectly right. At some point, you just have to concede that something is “widely considered,” so you can start somewhere. Once I had seen the entire exhibition it appeared to me that the museum team was way way ahead of me. Still, I’m compelled to acknowledge how hard I have often found it to tell the origin story of any movement.

One of my favorite parts of the opening gallery was a film showing the male parents taking over childcare while the women had meetings. The men, chain-smoking cigarettes and dandling children on their knees as they were interviewed, talked about how they wanted to support the movement for women’s liberation, and how they understood how much work a woman could put into keeping a home and raising children. When asked if they wanted to take over the childcare, they were honest about not wanting to do it all the time. As I watched several women walk through the museum galleries with their babies and toddlers, I wondered if the museum had a childcare service.

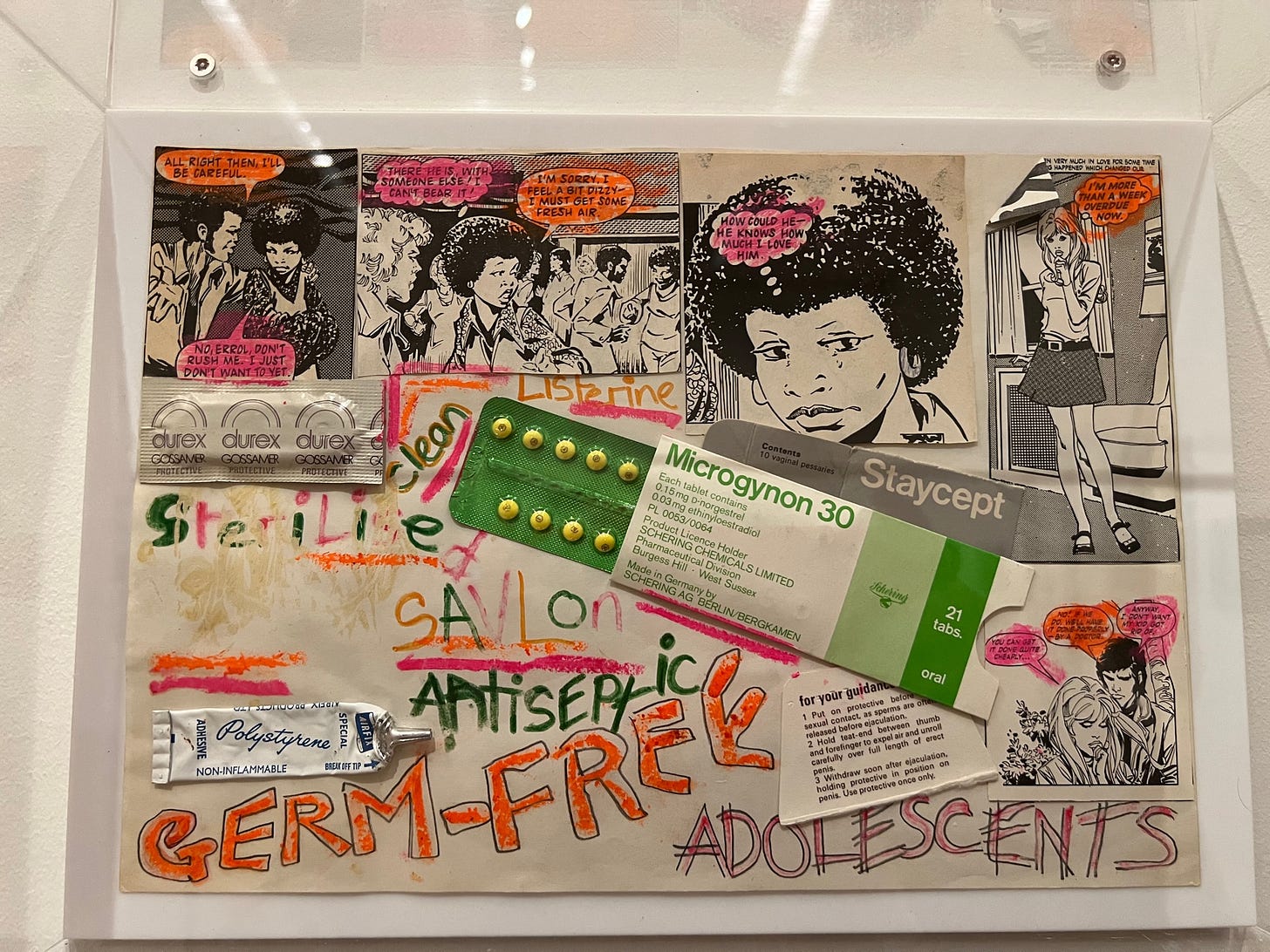

The section on punk rock brought back memories of poring over music magazines in record stalls at the mall. I’m fascinated by all representations of women in public, particularly the ones developed by women. I came of age in the 1970s, in an oppressive environment in the suburbs of Atlanta, Georgia. I was told going to hell for my queerness and rebelliousness. At high school I was a “weirdo,” which at that time in that place was code for any form of non-heteronormativity, and meant none of the adolescent social codes protected me. I was imprinted by, among others, UK punk rockers such as Poly Styrene, The Slits, The Au Pairs, and Siouxsie Sioux (who is arguably of a different milieu, but whose album The Scream was part of the soundtrack that motivated my escape from suburbia) as I read those magazines. They showed me that mockery of the status quo could be purposeful in addition to blowing off pent-up anxiety and rage.

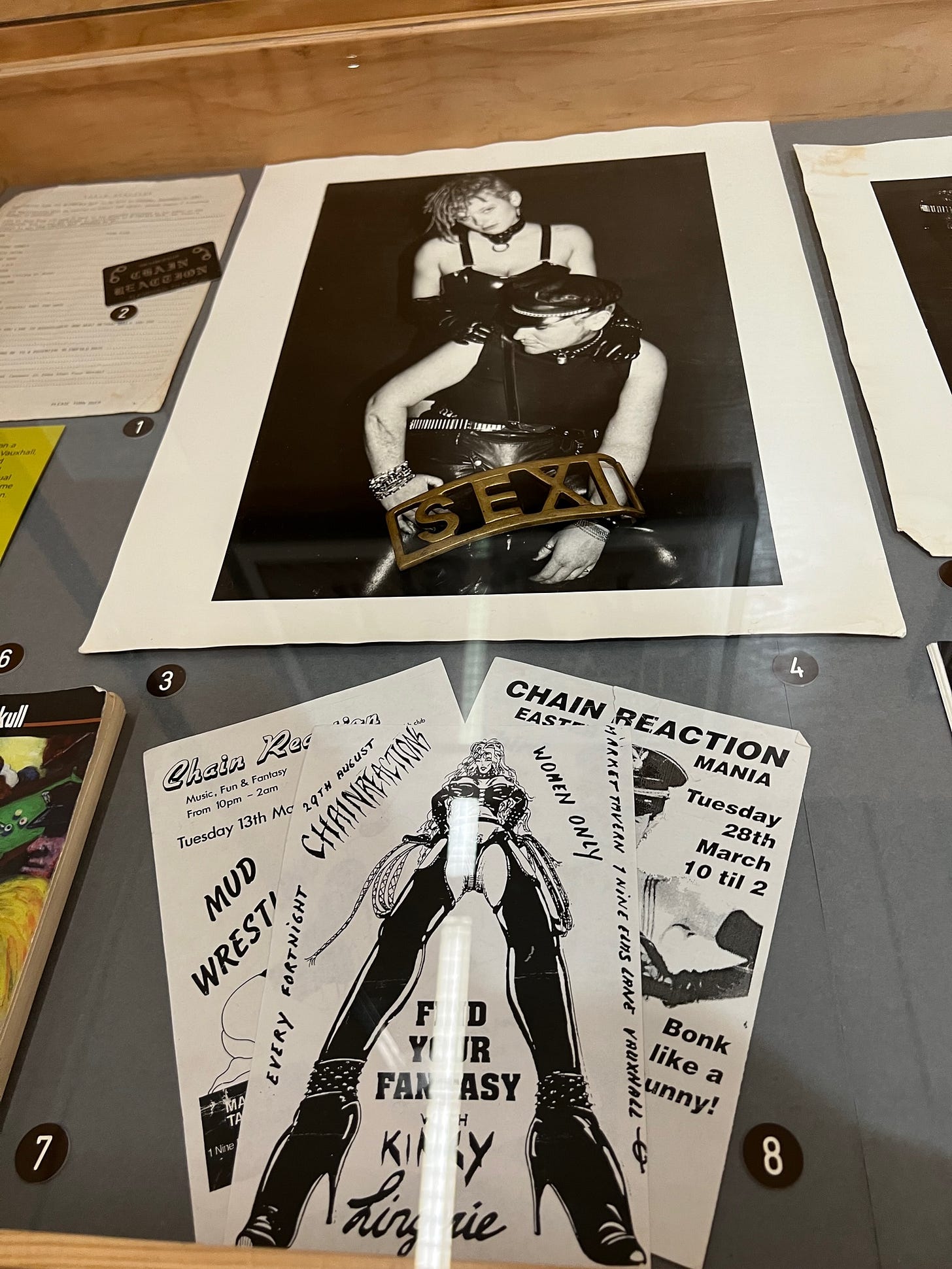

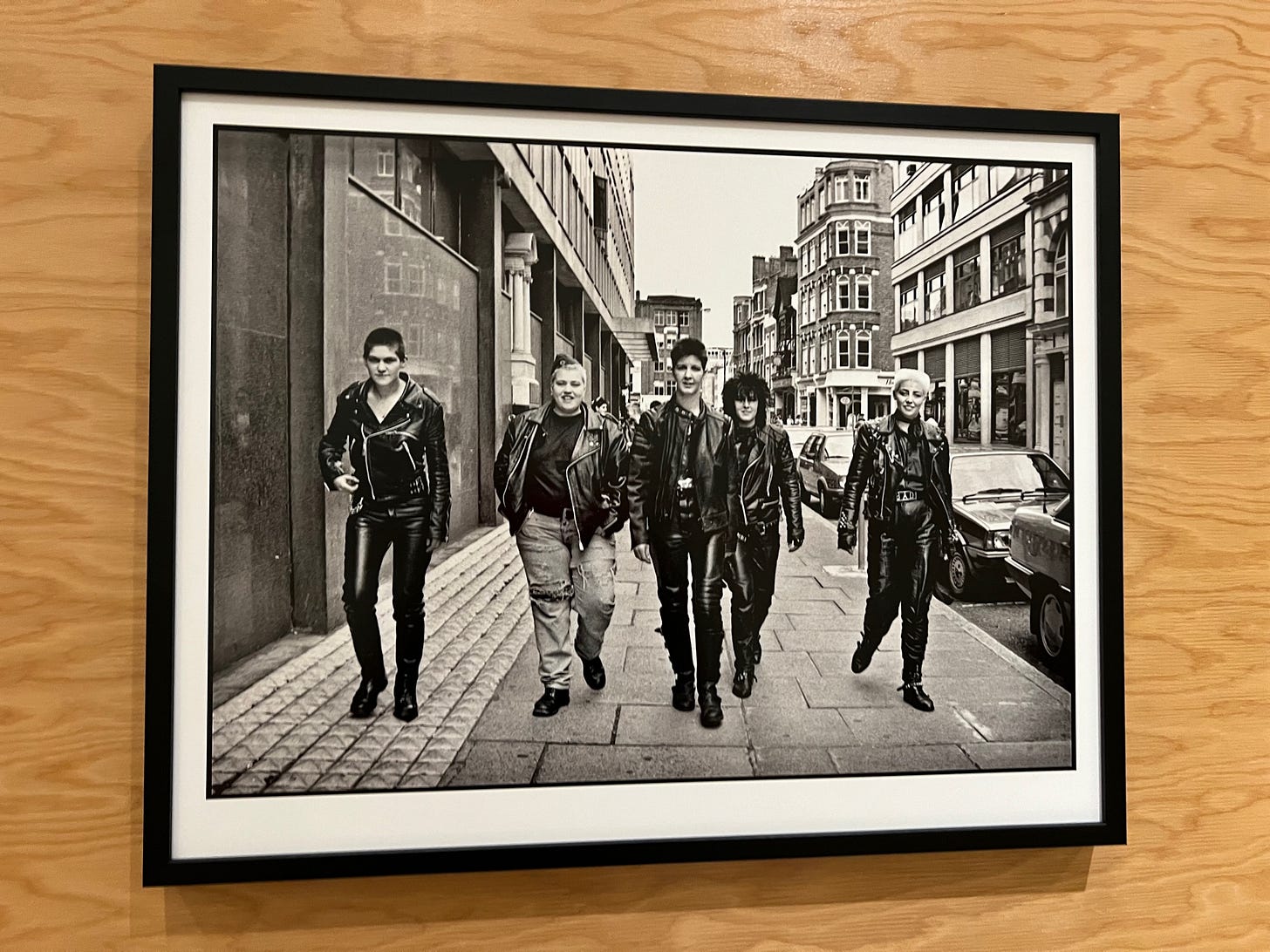

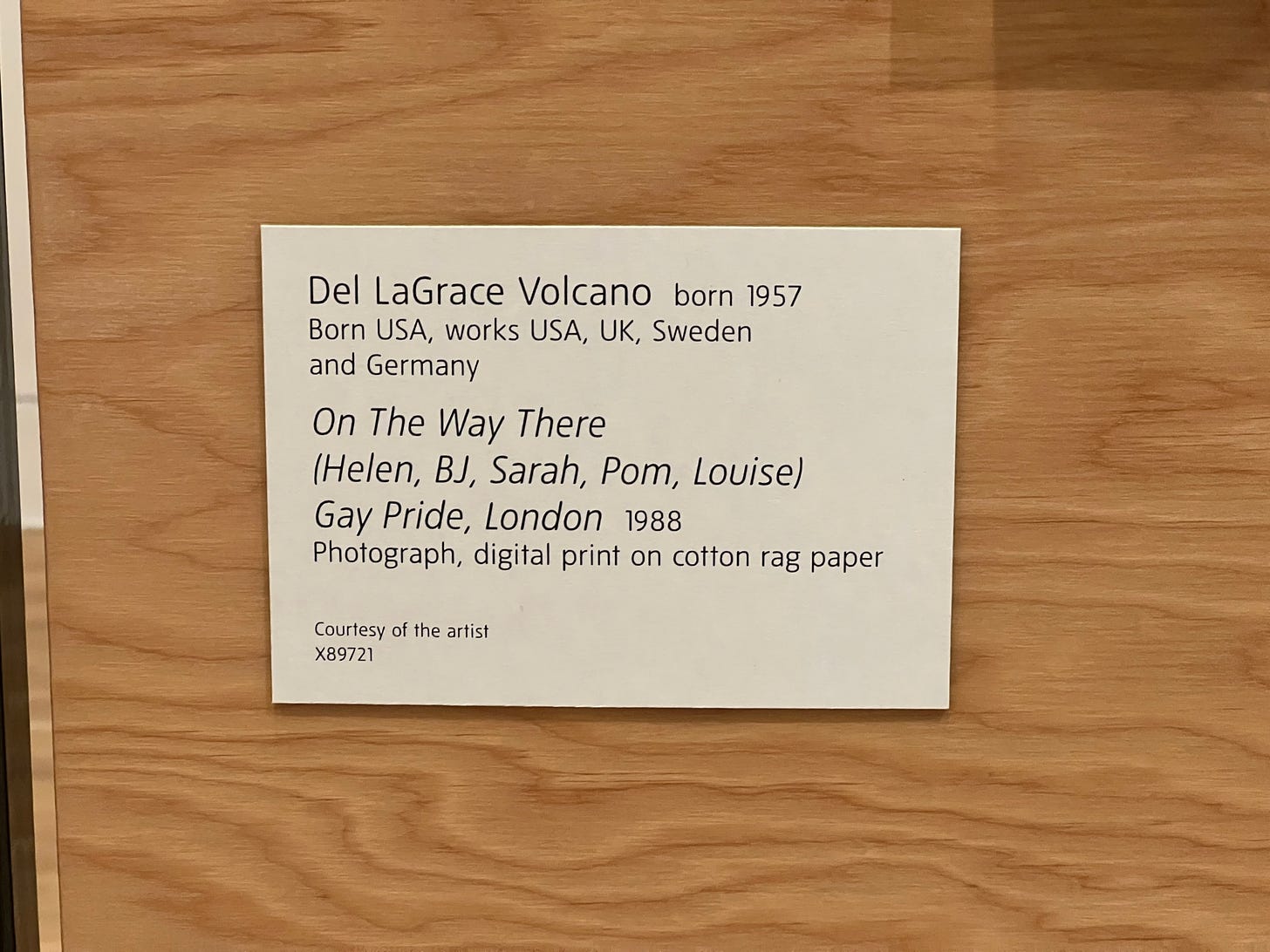

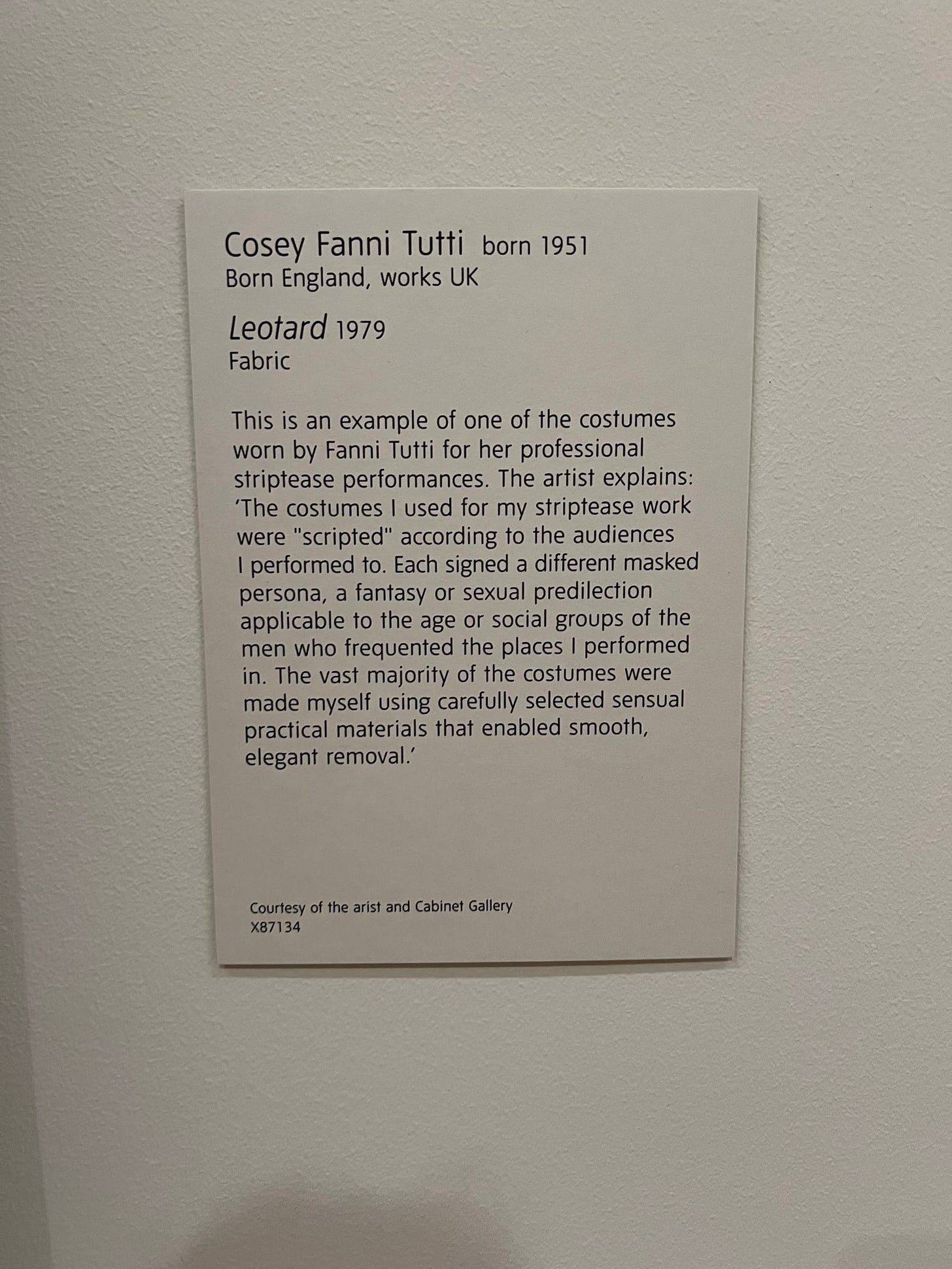

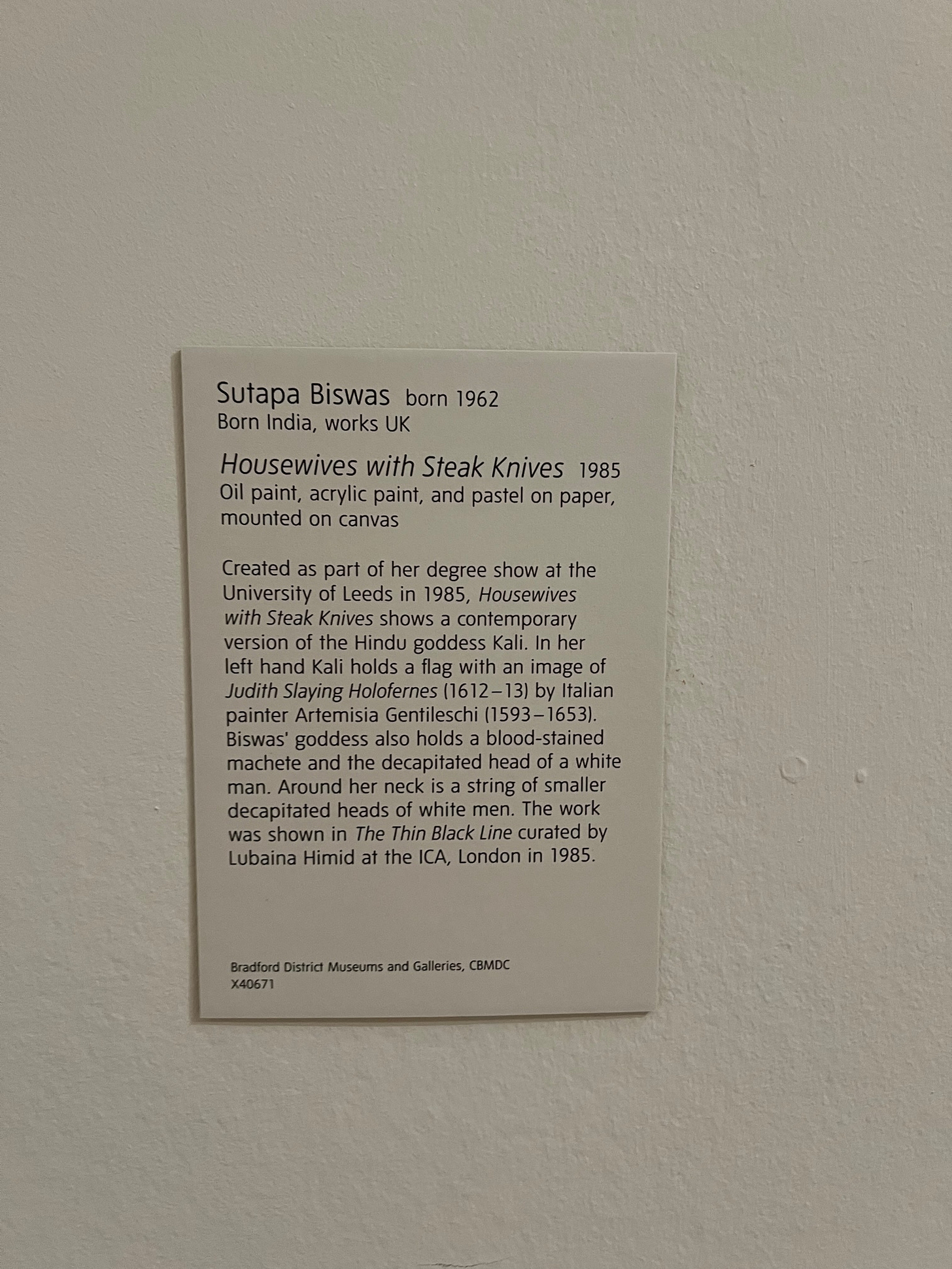

There were so many juicy items in the exhibition, and I can’t recommend it enough if you’re in London while it’s up. A few of my favorite items were a photo series by Del LaGrace Volcano called “Queer Dyke Cruising,” photos and a garment from Cosey Fanni Tutti, and a painting by Sutapa Biswas called “Housewives with Steak Knives,” hilariously printed on an apron sold in the museum shop.

From the museum’s website

https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/women-in-revolt :

The first of its kind, this exhibition is a wide-ranging exploration of feminist art by over 100 women artists working in the UK. It shines a spotlight on how networks of women used radical ideas and rebellious methods to make an invaluable contribution to British culture. Their art helped fuel the women’s liberation movement during a period of significant social, economic and political change.

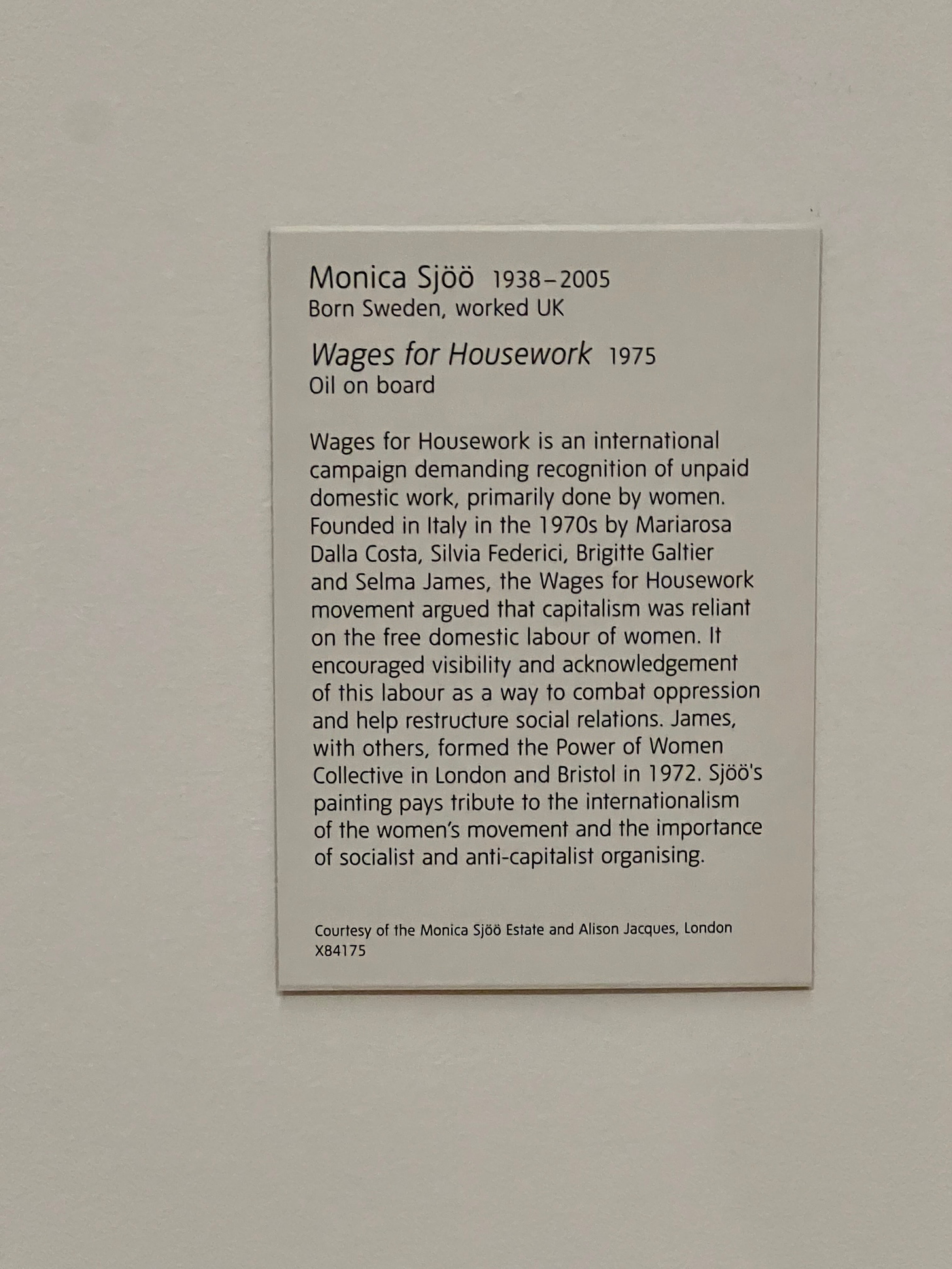

In the 1970s and 1980s a new wave of feminism erupted. Women used their lived experiences to create art, from painting and photography to film and performance, to fight against injustice. This included taking a stand for reproductive rights, equal pay and race equality. This creativity helped shape a period of pivotal change for women in Britain, including the opening of the first women's refuge and the formation of the British Black Arts Movement.

Despite long careers, these artists were often left out of the artistic narratives of the time. This will be the first time many of their works have been on display since the 1970s.

Through their urgent and powerful art visitors will encounter a productive, politically engaged set of communities, who changed the face of British culture and paved the way for future generations of artists.